How the social contract that governs live music went up in smoke alongside a historic Glasgow church

Surrounded by goths in a burning Glasgow church at an (aptly named) Sematary concert may not have been the way I expected to meet my maker, but as smoke clouded my vision and clawed at the back of my throat, I couldn’t help thinking how painfully on-brand it would be. At the front row, pushed against the barricade so hard my ribs bruised with their metal indentations, I wondered whether it’d be the smoke inhalation, the blaze itself, or the inevitable crowd crush that finally did me in. When the panic subsided and I realised the situation wasn’t life-threatening, another worry lingered: that a way of life as I knew it was being threatened. Not by fire and brimstone, but by members of my own community- Gen Z.

On 5 June 2025, emo-trap collective Haunted Mound performed their only Scotland date on their “Death’s Wagon” tour at St. Luke’s, Glasgow. The venue, built in the 1830s as a parish church, fell into disrepair before its 2015 refurbishment restored the stained-glass windows, arches, carved pillars, velveted balconies, and towering pipe organ. Modern sound and lighting were added for decidedly less holy events of up to 600 people. At capacity, St. Luke’s still feels intimate and underground- nothing like the impersonal enormity of the Hydro or SEC.

As the sun set, jewel-toned beams drifted across the gothic interior in striking contrast to Haunted Mound’s macabre aesthetic. Songs like “HAUNTAHOLIXX MIXTAPE,” “Slaughter House,” and “Gunsmith,” delivered in the monotone, emotionally flat style of SoundCloud trap popularised by Lil Peep and XXXTentacion, coupled with the niche yet tight-knit fanbase and e-goth coded venue, everything just felt right.

The group hadn’t performed in Scotland since 2019, making this a huge win for local fans, many of whom would’ve been too young to attend back then. Solo sets from lesser-known members like Anvil and Hackle built toward collaborative favourites before ushering in the headliner, Sematary. Alone, he could probably fill St. Luke’s with chronically online Tumblr alt girls, so a lineup this stacked sold out almost immediately.

When my friends (who had queued all day and kindly held a spot for me despite my last-minute arrival) weren’t let in, I should’ve known the night was cursed. I promised to bring them merch and wandered into the nearly empty venue alone. Thanks to them, and despite my half-second wait in the queue, I ended up with a prime spot on the barricade. Completely undeserved. Unheard of.

Alone, I befriended the kids beside me- “kids” because, to my surprise, they were only sixteen years old. I’d discovered Haunted Mound at that age nearly a decade ago and naively assumed everyone else had aged with me. Apparently not. Now, normally, I grab merch early; however, as the tide of angsty teens poured in, I knew leaving my spot meant losing it forever. Still, I asked if they’d hold it. Their horrified reaction, “uh… people are coming in, you’re gonna lose your spot, I would just wait,” was my first indication that something about this new crowd was just a little bit off.

For the record, I’m not so entitled to think strangers owe me favours, but across twelve years of concerts, festivals, underground metal shows, and everything in between, asking someone to hold a spot is standard etiquette. Everyone has let someone pass to rejoin their friends- it’s part of the social contract that keeps crowds safe. Defeated and slightly puzzled, I accepted that I might go home with a 3X T-shirt I prayed would shrink in the wash.

The show began uneventfully enough, and I was reveling in the moment, excitedly waiting for Sematary to appear onstage. When he finally emerged, the room erupted; we screamed the lyrics with the fervour of a people denied air itself- a feeling we’d soon experience literally.

At first, I thought I might be imagining it. Something was burning. I could smell it, faintly at first, then intensifying rapidly. Three songs into his set, I started filming one of my favourite tracks, capturing my initial realization of impending danger. In the video, I’m heard exclaiming: “Something is burning.” Someone beside me waves it off, stating, “It’s just the smoke machine.”

No it’s not, I thought. Almost on cue, a voice behind me confirms: “That’s not smoke machine smell- something is definitely on fire.” We stared at each other in alarm as everyone else remained unsettlingly unfazed.

Within seconds, I could barely see the stage through a wall of smoke no machine could produce. The music cut, the lights lifted, the performers looked confused- then the track restarted and the show carried on. I assumed things were under control, even as my brain replayed footage of famous crowd crushes and venue fires. As the smoke thickened and colonized my airways, I resigned myself to the idea that I might die in a burning church at a Sematary concert. Then the music cut again, and the lights came up fully.

I managed to capture the moment Sematary shouted, “Whoever lit a firework, fuck you,”

The group was led offstage. Security wove through the crowd, ordering an evacuation. Pinned at the barricade, I shuffled inch by inch past the merch stand, thinking I might at least buy something as a consolation prize, if nothing else. They said no.

Eventually, a side door opened and I slipped out, hoping they’d identify the culprit, clear the air, and resume the show. They didn’t. Instead, we were told to leave the property entirely- the show would not, in fact, go on.

I’m a big Hackle fan and was glad to have at least seen him, but for many of us, hopes of a full Sematary set were dashed as we were corralled out of the hazy church, eyes red, makeup streaming not from illicit substances but from stinging smoke and coughing fits. Anyone who didn’t already have asthma probably did after that night, myself included.

Outside, milling around with other bewildered fans, I learned the “firework” had been a flare set off in the middle of the audience dense enough to deem the venue a biohazard. Why anyone would sacrifice an entire hour of music for ten seconds of idiotic, ill-conceived theatrics escapes me. Was five seconds of internet infamy really worth it? Did he genuinely think anyone would respond with anything other than disdain

Online, the Haunted Mound subreddit lit up. Outraged disavowals, disbelief, and speculation flooded in. Users doxxed the suspected attendee, posting photos, recounting behaviours, and sharing allegedly overheard comments. As I scrolled through posts calling him “public enemy number one” and wishing him unspeakable violence, one thing was clear: fans were out for blood. I, too, was aggressively disgruntled, though in the hours and months that followed, my anger shifted away from the culprit himself toward what felt like a broader cultural shift.

Though furious at losing an hour of the show to one reckless individual, my accidental elder Gen-Z compatriot and guardian angel, Meg, rightly reminded me that leaving early was likely the best possible outcome. Packed into an ageing wooden structure with limited ventilation, clad in cotton band tees, a real fire could have been catastrophic. My paranoid “what ifs” were uncomfortably plausible. Ironically, the blasé attitude that unsettled me earlier was precisely what prevented the panicked crowd crush I so feared- and yet, most of the online discourse failed to address this very pressing reality, focusing instead on the injustice perpetrated upon those who paid for a full set.

The more I thought about it, the clearer it became that the flare was simply the extreme logical endpoint of behaviours I’d brushed off all night. The too-young crowd, the elbows, the phones. Early warnings I’d optimistically dismissed. From the moment my sixteen-year-old neighbours balked at holding a spot, I should’ve known this crowd played by different rules.

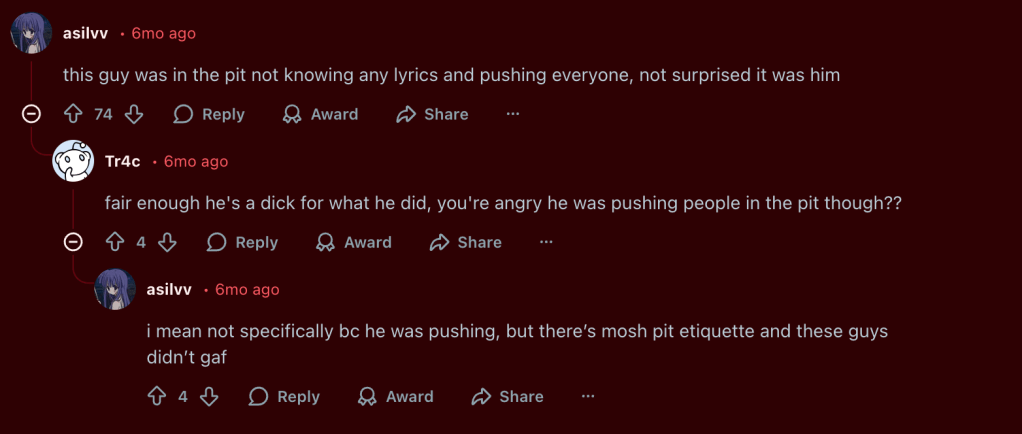

As a show ramps up, the audience usually does too- that’s part of the fun. I’ve been in enough pits to know what’s normal, and this crowd absolutely wasn’t. Seconds into the set, I was already wedged so tightly against the barricade I could barely breathe. Elbows jabbed and arms contorted around my head as everyone around me tried to shove their phones in front of every other phone to secure the perfect shot. How anyone captured anything but a blurry, split-second video is beyond me; spatial awareness simply wasn’t in the room with us. As one Redditor observed, “there’s mosh pit etiquette, and these guys didn’t gaf.”

Countless others confirmed my dark suspicion that, for some reason, common gig courtesy is dying out. “There’s a serious issue with the public at HM shows who don’t know how to behave,” wrote one user. Another, directly referencing the flare, added, “Those are for outdoor use only; it could’ve easily caused a mass panic.”

The consensus was damning: many younger fans seem to have no grasp of the unspoken social contract that keeps live music safe and communal. This wasn’t an isolated incident; it was symptomatic of a wider cultural failure.

In this post-COVID, Black Mirror-esque era, etiquette is eroding. It’s not just that young Gen Zers endanger themselves and others for TikTok- it’s that many genuinely don’t seem to know how to behave in these spaces. The line between rebellious chaos and outright disrespect has blurred beyond recognition. Much like the “pranks” that masquerade as harmless fun while targeting hospitality workers, this new breed of concertgoer sees ruining a show for hundreds as a quirky stunt for internet clout, and the impact on everyone else is an afterthought, if a thought at all.

Across the industry, artists are saying the same thing. Sabrina Carpenter had to stop a show because fans kept shoving forward just to get a selfie, asking the crowd, “Can you all just chill for, like, two seconds?” Chappell Roan recently pleaded with her audience to stop climbing barricades for TikTok angles because people were getting crushed in the front rows. Even Tyler, the Creator- who has famously tolerated mass pandemonium for over a decade- went off on fans for filming entire songs instead of participating, telling them, “This is weird, bro. You’re here. Be here.”

Then there’s the rappers dealing with what some have dubbed “projectile culture.” Phones, bracelets, vapes, even shoes launched onstage to the point that Drake paused a show to lecture fans after someone clocked him with a phone mid-song. Lil Nas X said young crowds “treat concerts like content farms now,” and Rina Sawayama halted a show after fans repeatedly forced themselves forward, saying “Someone’s going to get hurt.” After St. Luke’s, I see their point.

Psychologists studying post-lockdown behaviour note a measurable dip in social awareness among younger audiences, especially those whose formative years were spent online rather than in physical social spaces. One 2022 study comparing pre- and post-COVID concertgoers found that Gen Z fans were dramatically more interested in leaving with footage and quelling rumors of non-attendance than with memories of the actual show.

It dawned on me that the flare wasn’t the root cause; it was the natural culmination of an array of factors that had lain unaddressed for years. The crowd’s behaviour- the elbows, the refusal to hold space, the obsession with filming everything yet experiencing nothing, all pointed to a fundamentally skewed worldview. It feels like the muscle memory of being in public together has atrophied. If people can’t navigate a gig without selfishly endangering each other, what does that say about the direction we’re heading in?

I’m not anti-Gen Z, I’m quite literally one of them (albeit tenuously), but I can’t help but notice that something about this hyper-documented, clout-driven landscape has deeply impacted the culture that makes concerts feel like collective exaltation rather than a battlefield of competing personal broadcasts. If live music becomes nothing more than a backdrop for content, and the crowd becomes an obstacle instead of a community, then the flare at St. Luke’s won’t be a comical, isolated incident in the Glaswegian consciousness. Instead, what will continue to haunt the community is the unsettling sense that we’re losing the ability, or maybe the desire, to experience anything together at all.